Treating the untreatable

While the death of patients is a sad reality for their loved ones, they also take an emotional toll on the doctors and nurses who treat them. The following is an account of one such episode.

"Bharat, how many patients do you have?" Maria asked. "Can you please take care of this patient whom I am looking after now?"

It was a surprising question coming from a seasoned doctor at my hospital, who had never before asked me to take care of one of her patients.

It was a 62-year-old man who was found unresponsive in the group home he lived in after he had choked on a piece of sausage and had remained critical since. What complicated matters was that not only was the patient unresponsive to treatment but that he was also a potential organ donor.

She informed me that United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) had been informed according to hospital policy, as was the norm in the case of patients who had decided to donate their organs.

"I can take any one of your patients in return," Maria offered.

I hesitated as some of my patients were also not doing very well of late. In particular, the three patients who were assigned to comfort care only, meaning a withdrawal of all treatment and keeping them on pain killers, so they die peacefully.

For three consecutive days, I spoke to the anxious family members of three different patients with all the courage I had and informed them that their loved ones were dying.

The first of those was an 82-year-old woman, Mrs MS, who had mild dementia and had recently suffered a stroke, and was discharged, but was admitted a couple of days ago after a massive heart attack.

What made matters clear in her case was the fact that she had, in her days of clear mental state, executed an advanced directive NOT TO RESUSCITATE, meaning that in case she was unresponsive to regular medical help, no extraordinary procedures should be performed in order to keep her alive or bring her to back to life. She had clearly decided not to live in a vegetative state.

Though such a decision may be in line with the wishes of the patient, it can be very painful for their friends and family who care for them. Her three daughters were no different. They tried holding back tears in front of a stranger, a doctor, who was telling them that their mother is not going to be alive in a matter of hours to days.

I explained to them that their intelligent mother had wisely executed that advanced directive since she didn't want to live this way. They tearfully agreed and she was kept on comfort measures only.

The second patient was a 78-year-old man, Mr AR, of had suffered a heart failure and whose condition was worsening and had no hopes of recovery.

I had to talk to two of his brothers who were slightly older than him, one of whom was blind and they were living together in a townhome supporting each other. When I told the brothers that their younger brother was dying, the eldest, who had the clear vision, was in tears and said he cannot see his 'baby brother' dying.

The third patient, Mr FS, the oldest out of three, was a 90-year-old man with chronic heart failure and a cryptic coagulation disorder. It was equally draining emotionally as with the loved ones of the other two. But his mature daughter didn't need anything from me after I gave her the information that her father was not going to survive.

It was in the middle of caring for these three patients that Maria had made her request. But I agreed to take care of her patient.

The moment I walked into the 62-year-old's cubicle in critical care, I noticed that he was totally dependent on the ventilator. I checked for eye movement which was not there and noticed that he was not on any kind of sedation. His pupils were fixed and didn't show any reaction to light.

"Hello..Mr GS..." I called out his name, "Can you hear me?" to which his response was a motionless silence.

Somehow, I felt nobody was in there. I called Brook, the nurse taking care of the patient, and told her there was some crusting in the eyes, and that his eyes need to be kept moist and closed since his corneas may be harvested. She came back immediately with a small tube of artificial tears.

"Knock Knock".. a lady in her late thirties, who was slightly more made up than usual hospital visitors appeared at the door. She introduced herself as one of the Nurse coordinators for the UNOS.

She asked me whether I am familiar with the requirements of the UNOS in facilitating organ donation. I told I was not, except for the first time when it was introduced at the time of orientation to the hospital. She handed me a small booklet which briefly covered the standard hospital policy observed throughout the state and protocol to be observed to declare brain death. I went through the protocol and was satisfied that I had not forgotten.

Another coordinator from UNOS was sitting at the nurses' station. She was looking less friendly than the first lady and almost, ordered me to get a cerebral perfusion scan immediately so that they can hasten the process of organ donation.

I tried to hide my irritation with this hands down approach and told her that I have just assumed the care of the patient. I also told her that since it was only slightly more than 36 hours after stopping any kind of sedation, it would be too premature to do either a brain death protocol or perfusion scan.

She had most probably sensed my irritation and hesitated a bit. I told her since surgical harvesting of organs effectively removes all functioning organs from his body, we have to make sure that these protocols, which are there for a reason must be followed.

"Oh, one more thing, doctor. I was told that you want to speak to the family members of Mr GS. Can you defer it until the declaration of brain death?" the second coordinator from UNOS asked.

I told her since the patient was living in a group home for non-functional, or quasi-functional individuals who were totally dependent on other for activities of daily living, it was definitely appropriate to talk to the next of kin before the declaration of brain death. I added that according to my understanding, the patient didn't have a driving license, and was not capable of taking a conscious and educated decision regarding organ donation.

The day went fast with rounds and seeing new admissions and checking up on all four of my dying patients.

Heart of Mr GS in critical care who was about to donate his organs was still ticking. There was a change in the nursing staff and, Danny, the 50-year-old Philipino nurse was there taking care of him now.

I transferred the calls to my cell phone in case there was any new development in the night. I went to the Telemetry floor and met all three patient's families by the bedside and made sure they were pain-free.

Mr GS's brother and sister-in-law had flown in from Texas that evening. They were very calm, courteous and understanding as I explained to them how Mr GS had ended up in this situation, and that in the light of observations so far, it was almost certain that he was brain dead. They agreed to sign the papers necessary for organ donation.

Around 11 PM, when I was getting ready to go to bed, Caroline the night hospitalist called, to tell me that Mr GS had a low urinary output, and drop in haemoglobin, which was unusual. After she told me the other details I asked her to start the patient on vasopressin. She informed that she had already done so.

Next morning, Mrs MS, my patient who had suffered a heart attack died peacefully 48 hours after starting on comfort measures. Family members were extremely sad, but her daughters thanked me and the nurses, for what we had done. Meanwhile, my concentration went back to Mr GS and I ordered a scan to check on him.

Mr GS had his cerebral perfusion scan which was suggestive of brain death in appropriate clinical setting. At about 72 hours after stopping all sedation, I performed the second brain death protocol and we were convinced that there was no response. In the absence of any brain stem reflexes, 2 EEGs showing no cerebral wave activity, cerebral perfusion scan suggesting brain death, and 6 minutes of stopping mechanical ventilation failing to trigger any respiratory activity, I declared Mr GS brain dead.

I had a feeling I saw tears in the eyes of Brook, the nurse who was taking care of Mr GS since morning. I conveyed the news to the UNOS representatives. They looked a little relieved and hurried back to their temporary office with open computers, established in the far corner of doctors' dictation area in critical care. I was told probably they were not going to harvest his heart because of the cardiac arrest he suffered en route to the hospital.

When I returned in the morning, I had my sign-out from the night before. Mr AR, the gentleman with refractory heart failure and LV had died peacefully in the night, and Mr GS was taken in the morning to the OR for organ harvesting. Surgeons from all over the country had flown to our little midwest town and were currently operating on our patient.

Before I could take the lunch break, around quarter to noon, Cynthia, the nurse looking after Mr FS, called me to tell me that his monitor was showing a flat line. I rushed to his room and saw that his daughter was sitting by his bedside holding his hand.

I told her "I am sorry, your father passed away". "I know," she said softly and turned to me and Cynthia. "I thank you both and all the nurses who made really painless and peaceful".

Suddenly I felt empty, just like the family members of my patients who lost their loved ones. I have seen deaths of my patients, held hands, given hugs, and consoled families. I have seen deaths of my family members as a grown up man.

However, four patients dying on my watch within four days was overwhelming. Driving back home that evening, I was sad and tried to console myself that in the unfortunate event of having to declare another patient brain-dead, I am better informed now, and have the experience of going through the protocols.

I reached home, finished my late supper and went to bed thinking about the next two days work and planned the journey to Orlando for a reunion, and the excitement of meeting old friends. I remembered that all of us from the Class of 84 had turned fifty, now! I think it is a good thing to start at 50 something afresh.

After returning from the reunion, I was told that both kidneys, liver and corneas of Mr GS were harvested and at least four patients were given a lease of life with his organs. Also, tissues were collected for studies.

Our critical care nurses received a 'Thank you' card from the UNOS.

OneIndia News

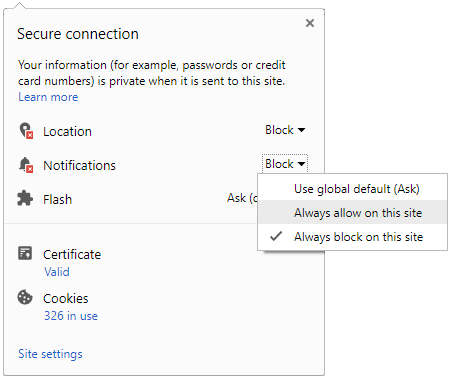

Click it and Unblock the Notifications

Click it and Unblock the Notifications