The farmers of Yamuna khadar: a manifesto for urban farming

A city's image directs its development. The ways in which its residents look at it, look at themselves as part of it, these inform the trajectory of growth a city aspires to take. Image-making has always been central to city-making: the myth of the individual self, bound as this and not that, is at the heart of the myth of the collective self. A city often defines itself by and through exclusion just as an individual and a group consolidates its notions of itself as being some things, some traits, some occupations, and not others.

Such is the fate of farmers in Delhi. The national capital, a city of many cities, dilwaalon ki Dilli, unloved city, rape capital, these and similar monikers have framed Delhi in contemporary popular imagination. Each of these envisions a particular worldview, crystalizes a particular way of looking at the city: all of these function together, in active contestation-and consort-with each other, to determine the kinds of politics, policies, and practices which give shape to Delhi as both idea and lived reality. None of these, however, have any space or scope for farming: the fact that Delhi is a historic city, that it has more villages than perhaps planned colonies, even that it has very poor land and property records, all of these should alert us to the rurality at the core of our multifarious urbanity.

But even amongst this group-or category-of residents, there are key distinctions. Within the 1,483 sq. km. which constitute the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCTD) are 224 rural villages as per the Government of NCTD's Revenue Department. These are distinct from notified urban villages, like Hauz Khas; many of these are in the peri-urban districts of outer Delhi, such as Narela and Najafgarh. They continue to observe farming and allied agricultural activities as their core occupations: in 2014-15, the Economic Survey of Delhi identified approximately 343.12 sq. km. of land as total cropped area and an estimated 231.50 sq. km. as net sown area. In other words, these are farmers and rural communities with due recognition from various arms of the state: their land records are well-maintained, have even been digitised; their landholdings are subject to the Delhi Land Reforms Act, 1954; and their productivity-and seasonal and other threats to it-elicits concern from both the GNCTD as well as a gamut of elected representatives. Various schemes have been launched for their welfare over the past few decades, and they are recognised as legitimate contributors to Delhi's economy, society, and culture.

This is not the case with farmers at the other end of this legitimacy spectrum. These are small, scattered groups of agriculturalists at the periphery of the state's gaze and the citizenry's aspirations. Their landholdings are tenuous, subject to intense contestation for close to three decades now: their livelihoods, rooted to the earth they till, are seasonal with the ebb and flow of demolition and eviction. Their history, as a community, as farmers, is old though: almost as old as independent India, older certainly than most institutions who threaten them with the cold, black letter of the law. Their legitimacy, and claims, derive from this history, rooted to the city, rooted to the soil and the land which has made the city. Much maligned, almost unknown, these are the farmers of the Yamuna khadar.

It is a sign of the times that everybody cares about the, but nobody actually knows it. In Delhi, the 22 km stretch of the river's floodplains-its khadar-have been put to varying use and are the subject of considerable controversy and contestation. Amongst these, downstream the Loha Pul-the old cantilever bridge spanning the Yamuna off Salimgarh-exist four revenue estates by the names Bela, Indrapat, Chiragah (North), and Chiragah (South). The emergence of these estates can be traced as far back as the Mutiny of 1857, when considerable land of the Mughal state and court was confiscated and entrusted to the newly-constituted local government under the Commissioner. These estates, nazul or crown, changed jurisdiction multiple times over a century, from the Commissioner to the Delhi Municipal Committee (DMC) in 1874; to the Nazul Office in 1924 and later subsumed within the Land and Development Office (L&DO); to the Delhi Improvement Trust (DIT) consequent to its formation in 1937; and, finally, to the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) at its institution in 1957.

It was under DIT in 1949, at the height of the cooperative movement in Delhi, that these four revenue estates were organised for farming and dairy purposes under the aegis of the Delhi Peasants Cooperative Multipurpose Society (DPCMS). Inspired, possibly, by the 'Grow More Food Campaign' which ran during the Second World War and by the need for greater food security given the refugee crisis after Partition, as much as 14.29 sq. km land comprising these four revenue estates was leased out to the DPCMS. Society members evolved internal mechanisms for land allocation under the broad rubric of the cooperative byelaws, and a variety of staple, vegetable, and cash crops were grown by the banks of the Yamuna. This arrangement continued for many long decades, even after DIT's dissolution and its replacement by the DDA: revenue records, including records of rights, exist well into the twenty-first century, as do rent receipts and a parallel paper trail of various documents establishing residency and occupation.

Meanwhile, as Delhi grew around yet away from the Yamuna, the city gradually forgot its core, forgot the land which it acquired and usurped to make space for itself. The root of modern urbanity is a wilful ignorance, the misremembrance of the source and seed of one's conveniences. If Delhi saw only taps and supply lines but chose to ignore the river which made these possible, it also saw food and marts and chose to ignore the earth and effort which gave birth to these necessities. Along with the Yamuna, the farming communities along its banks have also suffered from this mixture of disinterest and disregard: as the river grew excessively polluted and became divorced from the city's daily life, so too has farming along its banks been delegitimised as unauthorised squatting, as a source of pollution, as an aberrant eyesore. While DDA terminated the lease to DPCMS in 1966, the society itself continued taking rent from its members till 2010: just a year before the first round of demolition of crops and homes made the farmers rudely aware of the precarity of their situation. Though notices under the Public Premises Act, 1971 were first served by DDA in 1991, DPCMS's rent collection till 2010 along with provision of civic amenities and primary education and healthcare infrastructure by various government agencies gave a measure of certainty to the farmers with reference to their vocation in and settlement on the land. Since 2011, however, they have been criminalised through many demolitions and much litigation as not just squatters on public land but also sources of riverine pollution and food-chain toxicity: this is despite their layered claims to legitimate occupation and regardless of comprehensive water and soil testing all along the Yamuna's khadar. The riverfront, in planning terms, too has gradually become a valuable asset, to be cleansed and beautified for the greater public good: farming is now a roadblock in these world-class ambitions in millennial Delhi.

It is time to revisit these ambitions though: it is high time to reframe the terms of the debate. On one hand the Indian state is committed, at all levels, to sustainability, to food security and to the protection of small and medium agriculturalists. On the other, it is also oriented towards remaking our lived realities in an image resplendent with the glow of power, success, and luxury. Growth, in and of itself, will not be our panacea: development, if and of itself, will only worsen the lot of those many millions who are yet to access the fruits and joys of the new millennium. Even as we advocate urban farming and champion rooftop gardening, we are unable to stem the flow of farmer suicides, to bring a measure of stability to a sector which employs most of us but pays steadily diminishing dividends. In Delhi, in the Yamuna's khadar, the problem is the solution: it has been begging for redressal and attention for almost a generation now.

We need to move beyond the narrow lure of legitimacy to more participatory, inclusive images of our cities. There has been farming and agrarian societies along the Yamuna's banks for almost seven decades now. For almost as long as India has been a nation, these communities have provided Delhi with ready grain, vegetable, and milk. They have contributed to our food cycle, lessened our dependence on external sources of sustenance. They have prevented the concretisation of the Yamuna's floodplains, been a green buffer against the channelization of the river. Self-sustaining and resilient, farmers along the Yamuna's khadar in Delhi have borne the brunt of multiple demolitions and recurring criminalisation of their livelihood to continue doing what they do best: share through sweat and blood the gift of food with all of us. It is high time that all of us, as a city, recognise their contribution to our lives and habitat. It is time we recognise the unique potential farming has in not only keeping the Yamuna's floodplains green and productive but also in supporting alternate forms of livelihoods and occupations which keep us grounded to our roots. In a city in which regularisation has been a byword for development, it is not impossible to reimagine a greener, more self-reliant future where we look amongst ourselves to resolve our problems: where we develop the strength to not just grow but also nurture a greener, more inclusive future.

Graphics by Nidhi Sohane

(Anubhav Pradhan is a researcher working on various aspects of Delhi's contested urbanisms. He has done archival and ethnographic work on and in Bela Estate)

(Chetan is an Assistant Professor with the Department of English, Bharati College. He was born and continues to live in an agrarian family in Bela Estate)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are the personal opinions of the author. The facts and opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of OneIndia and OneIndia does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

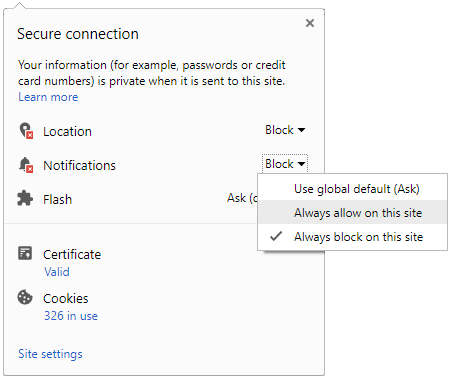

Click it and Unblock the Notifications

Click it and Unblock the Notifications