British raise army in Afghanistan's Desert of Death

CAMP TOMBSTONE, Afghanistan, June 23: The British officer grins with pride as he tells of building an army from scratch in the Desert of Death.

Captain Nigel Booker holds hands a traditional sign of male affection as he walks with his Afghan counterpart, Major Hamid Ullah, a grizzled ex-Mujahideen fighter who has been waging guerrilla wars for all of Booker's own 29 years.

''What he doesn't know about warfare hasn't been written,'' Booker says. ''And don't let him play you at draughts. He's murder.'' Nearly five years after the fall of the Taliban, British paratroopers are only now deploying as the first large international peacekeeping force into the volatile south of Afghanistan.

But the key to their plan to impose security in Helmand a vast lawless province of desert, towering mountains and narrow river valleys that grows nearly a quarter of the world's heroin opium crop is to raise a new Afghan army brigade to take their place. It is no simple task.

Four months into an 18-month plan to create a 3,000-strong force for the province, more than a third has been raised.

But of the 1,177 now on the books, 250 are absent without leave, having failed to arrive from training in Kabul or wandered off.

Still, the British say they are slowly producing a surprisingly disciplined force, and having a wonderful time doing it.

''They are about two months out of training and they're in an insurgency, holding their ground to a very high standard,'' said Lieutenant-Colonel David Hammond, commander of the British mentoring team.

''They're bloody great company as well.'' WASTELAND The Afghan army in Helmand is based in a remote wasteland, known in Persian as the Desert of Death, at a brand-new 68 million dollars camp, named Camp Tombstone by the Americans who built it.

But with the local governor pleading with the British to deploy the new force quickly, many have already been dispatched to forward operating bases in populated mountain valleys.

At the forward bases, small groups of 10 or 12 British troops live alongside 10 times their number of Afghans.

The Afghans drive in convoys of donated American Ford pickups. So far, six Afghan soldiers and one British mentor have been killed in Taliban ambushes.

Their commander says the attacks are a sign their presence is being felt.

''The enemy are smart. They want to attack British and ANA forces,'' said Colonel Muha Din, commander of the Helmand brigade. The key to the Afghan National Army's success, Western nations hope, will be its diversity in a country of countless rival ethnic groups and languages. The force is recruited countrywide and trained in a US-designed programme in Kabul. Units are carefully formed under a quota system to ensure that each reflect the overall ethnic mix of Afghanistan.

Colonel Muha Din comes from Herat in the west. His second in command comes from Paktika in the east.

He has been holding meetings with the locals in Helmand to explain the concept.

''There has been fighting in Afghanistan for 25 years, and they think we are just like the people who have been robbing from them, taking their money.

''We tell them -- we are the Afghan National Army. We don't represent one province. We represent all of Afghanistan.'' MENTORS Each Afghan officer, down to the platoon level, is shadowed by a British mentor, usually an officer or sergeant one rank lower.

The Afghan officers are a mix of veterans of the old Soviet-backed army and the countless Mujahideen guerrilla factions and militia that fought them, and among themselves, during 23 years of war.

''We teach them systems and logistics,'' said Booker. ''When it comes to actual war fighting, there's nothing we can teach.'' The relationship between the British mentors and their Afghan colleagues is far more intimate than in Iraq, where a much larger local force was rebuilt far more quickly.

Booker sings the praises of the goat stew and fragrant rice eaten with fingers in the mess hall. He treasures a gift, given by one of the Afghans, of an antique rifle that was used to fight the British a century ago.

''This is by far the best job in the world,'' he says.

Inside the barracks over aromatic tea, Booker introduces some of the men. Abdul Rahman tells the story of how he survived the Taliban ambush of his convoy, in which six of his comrades were killed by a roadside bomb.

Other comrades gently mock his awkwardness with the language, and he laughs.

An ethnic Uzbek from the remote north, he has learned the army's language, Farsi, only since joining the first member of his family to speak anything other than Uzbek, he says.

''Here we are all Afghans.''

Reuters

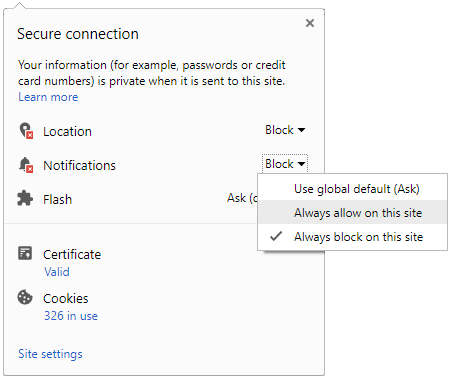

Click it and Unblock the Notifications

Click it and Unblock the Notifications