Salt merchants learn to survive Ethiopian desert

BERAHILE, Ethiopia, Mar 10 (Reuters) Like his father, grandfather and generations before them, Berhe Amare has spent his life walking camels along treacherous caravan routes from Ethiopia's Afar desert to the Tigray highlands.

His two-week treks are made in blazing heat with thieves and thirst equal threats, but Amare does not complain.

''It is a good business,'' the salt merchant says, clutching a walking stick and adjusting his headgear to keep out the dust.

''But we become very weak as the journey is difficult due to the temperatures.'' His eight camels pick up blocks of salt bought from mines along lakes below sea level for 1.5 Ethiopian birr (0.18 dollar) each.

After walking through the desert and up barren mountains into the Tigray, he sells them for between six and 10 birr each.

With each camel able to carry up to 30 of the slabs, that's enough profit for the father of four to get by in one of the poorest regions of Ethiopia.

It was in this hostile terrain that five European tourists and eight Ethiopians working as guides, translators and drivers were recently kidnapped by an unidentified armed band.

Among myriad possible motives for the capture, one theory among locals, diplomats and experts on the region is that it may be somehow linked to the Afar people's efforts to ward outsiders off their salt business.

Though now destined only for domestic use or livestock, the salt bars used to play a big role as currency.

''The salt trade goes back to early times. It is first recorded in the 6th century by an Egyptian traveller, but it existed long before,'' said Ethiopia-based historian Richard Pankhurst. ''Up to 1930, it was still used as currency.'' 'HELLISH FLATNESS' The modern merchants and their camels face multiple perils.

First, there is the heat: temperatures reach 50 degrees Celsius (122 Fahrenheit) down in the Danakil Depression, the Afar region's lowest point.

''We can't carry enough water, so we rely on the streams, but sometimes they are dry,'' says another salt trader, Hadush Abay, pointing at an empty riverbed as he pauses in the middle of a large train of about 60 camels.

''Some people fall down, get sick, and sometimes die. This is very risky work.'' Thieves also prey on the traders from time to time, normally forcing them to hand over money rather than the cumbersome bricks of salt. Although the traders want to take guns for self-protection, local authorities prohibit that.

For food, the traders rely on bread they cook along the way and sugar to keep energy levels up. They often walk in the moonlight when it is cooler.

The few foreign aid workers, researchers or tourists who venture there struggle to cope. Armed guards and dehydration salts are essential. Even some locals die along the way.

Due to the lack of vegetation en route, the camels also carry sacks of straw on their backs for their own sustenance.

''The journey is, by common consent in Ethiopia, one of the toughest trials a man can face,'' wrote British writer Matthew Parris, who went to the Afar last year.

''As you leave the comparative cool and civilisation of the Ethiopian highlands, and before you reach the hellish Martian flatness of the salt-pan-and-desert basin of the Danakil Depression, you must pass on your descent a place of sharp, dry mountains, cruel acacia thorn trees and winding, waterless riverbeds.'' None of the salt-traders met by this correspondent knew where the hostages -- including three British men, an Italian-British woman and a French woman -- were.

''I can only say, if they are out there somewhere, God help them, please,'' Abay said, pointing at the desert expanse below.

REUTERS

AD

BD0911

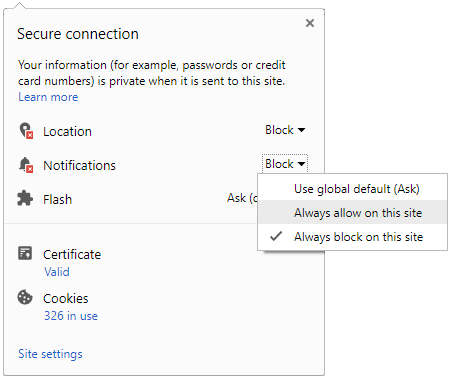

Click it and Unblock the Notifications

Click it and Unblock the Notifications