Barefoot midwives help Mexican doctors save lives

CUETZALAN, Mexico, Nov 21: From cutting the umbilical chord to post-natal surgery, giving birth in the remote Sierra Norte mountains of central Mexico used to be a dirty and dangerous experience.

''We had nothing, not even scissors,'' said Josefina Amable, a 56-year-old Nahua Indian, as she set out shoeless from a mountain hamlet to see a heavily pregnant patient. ''We used a machete cleaned with rum and needles for sewing clothes.'' Since before the Spanish conquest of Mexico, hardy midwives like Amable have trudged barefoot through the remote sub-tropical mountains, bringing babies into the world armed with bundles of herbs and centuries of hand-me-down wisdom.

Now, under a government pilot program mixing high-tech with sacred tradition, these midwives -- often the only people many women trust in one of Mexico's poorest regions -- are helping doctors keep mothers and babies alive, while picking up new tips from modern medicine.

Struggling to draw inhabitants of non Spanish-speaking areas lacking basic services into a health system many mistrusted, officials in the heavily indigenous central Mexican state of Puebla enlisted some unconventional help.

In five clinics attached to rural hospitals, medicine-men, midwives and village osteopaths or 'bone-men' work alongside conventional surgeons, radiographers and obstetricians.

Stocked with curative herbs and equipped with altars where healers perform cleansing ceremonies, the clinics entice Indian patients into the hospitals, where conventional doctors can also detect and treat graver ills.

''We want to be a bridge between traditional and conventional medicine,'' said Margarita Alvarado, administrator of the clinic in the cobblestoned coffee-farming town of Cuetzalan, set up five years ago, the first under the program.

The Nahua midwives, who speak little Spanish and shun shoes, cut maternal and infant death rates by bringing mothers in for check-ups and convincing them to give birth in a hospital rather than at home, doctors say.

PAST MEETS PRESENT

The clinic hummed with consonant-heavy Nahuatl one recent morning as pregnant women wearing embroidered Indian blouses waited in line.

In one room, 66-year-old midwife Michaela Perez muttered a prayer in Nahuatl, massaging the belly of a supine 28-year-old whose baby she had recently delivered.

Many mothers-to-be visit the clinic to treat ailments like fright' and 'evil-eye'-- afflictions they believe can be caused by evil spirits or spells.

''You can't explain 'fright' scientifically,'' said Alvarado. ''But I've seen women with it and here we cure it.'' A specially adapted delivery room has a metal frame women can grip to give birth in a traditional squatting stance. But with the midwives standing by, expectant mothers who may never have even seen a computer are also unfazed by ultra-modern treatments that might otherwise scare them.

Leonor Vazquez, a tiny old woman in a billowing lace blouse, filed three young women one after the other into a gynecologist's surgery where they sheepishly watched their babies' hearts beating on a grainy ultrasound screen.

MORE THAN A MIDWIFE

From early pregnancy, midwives virtually adopt the mother-to-be as their own daughter. As well as caring for her physical health, they cook up meals to satisfy cravings and provide a shoulder to cry on.

Babies were traditionally delivered at home, and the midwives command huge respect in Nahua villages, often stepping into family quarrels that upset their patient or telling off a father-to-be who is not taking his responsibility seriously.

But they help doctors save lives by spotting key danger signs while on call in remote areas, a skill vital in all-too-common instances when the hips of girls as young as 12 are too narrow for birth except by caesarean.

''If the midwife doesn't bring them in, they die,'' Diana Carpio, director of traditional medicine for Mexico's Health Ministry in Puebla state, said during a visit to Cuetzalan.

In a hut made of plastic and wood and hidden among dark-green coffee bushes outside Cuetzalan, nine-month pregnant Michaela Ramirez, 32, lies on her back as midwife Amable listens to her baby through a metal ear-trumpet pressed to her swollen belly.

Ramirez lost her last baby just as she was due, and Amable told her firmly in Nahuatl that when she felt labor pains she needed to come ''to the hospital where the doctors are.'' The government officially recognized traditional medicine for the first time in September, a move Carpio hopes could see the project implemented in indigenous areas nationwide.

Under new plans, midwives normally paid with small change, vegetables or even a goat, would earn a more steady wage and have better training in the ways of modern medicine.

Amable said she was glad she no longer needed to use tools like machetes in her job, but said that there was one concession to modernity she would never make.

''In sandals I would slip in the mud,'' she said, looking down at her calloused bare feet while striding through a lush valley to a patient's house. ''This way I can dig my toes in.''

REUTERS

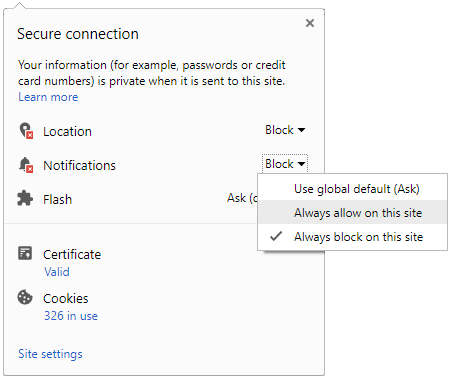

Click it and Unblock the Notifications

Click it and Unblock the Notifications